Preface: the following series is adapted from a collection of emails I wrote during a recent global health elective I did as part of my medical residency. It deals with issues pertaining to healthcare delivery and equity, specifically regarding the care of children with neurological illnesses. My hope in sharing these posts is to bring awareness to these topics and offer a glimpse into life in a country where readers may not otherwise have the opportunity to visit.

Dear friends and family,

As of Saturday evening, I’ve arrived in Conakry, the capitol of Guinea in West Africa. I will be here for the next month on a global health elective through my residency program. The purpose of my visit is to provide treatment and advance data collection for a research project interested in understanding the etiology of meningitis and encephalitis in the region. To do so, I will be working at a local hospital to help identify pediatric patients suffering from these conditions, performing lumbar punctures to diagnosis them, collecting samples of cerebrospinal fluid, starting treatment, and eventually sending these samples to a partnering laboratory in the USA that will perform fancy genetic testing on them. However, as there are no pediatric neurologists in this country (NB: I am still in the pediatric training phase of my five-year pediatric neurology residency program), I will also be referred children suffering from various neurological conditions of which the doctors in this country do not have comfort managing. Fortunately, there are some colleagues at home who will be remotely ensuring that I do no harm to these patients.

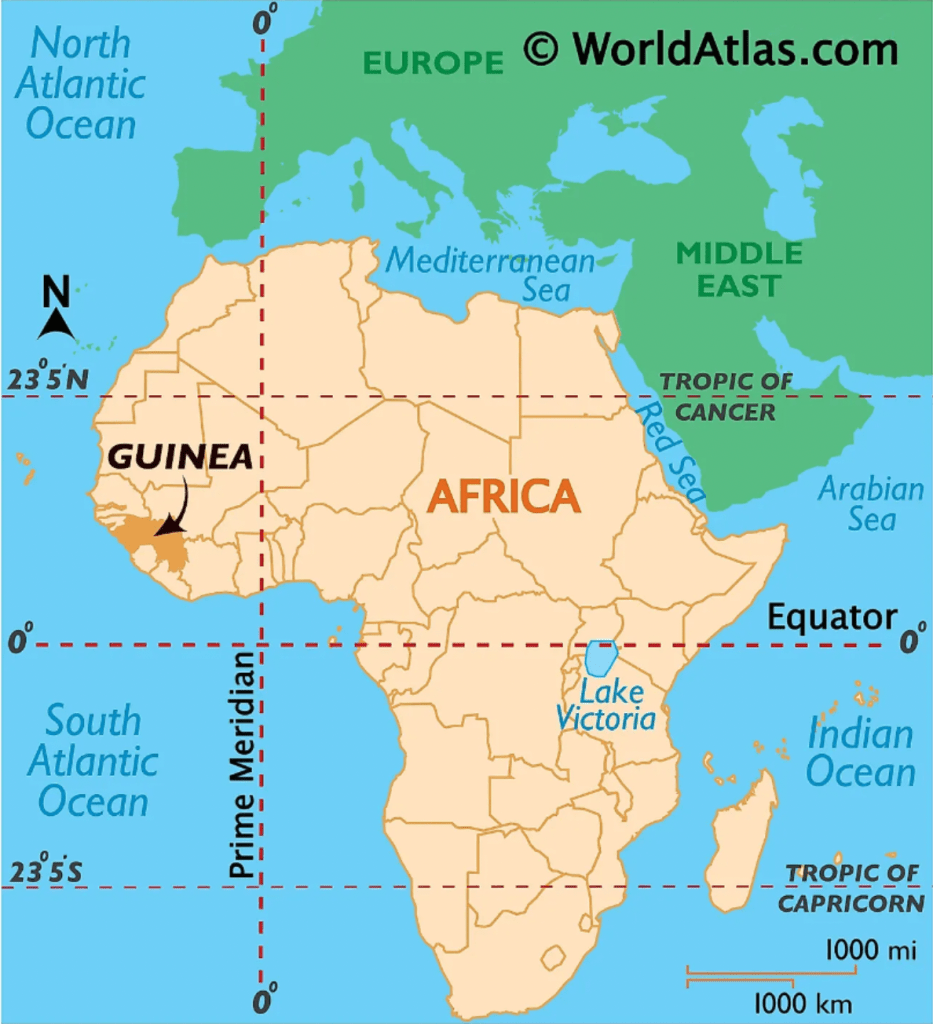

For those of you who (were like me and) do not know where Guinea is, below is a picture of the African continent that highlights the country (fun fact: there are four countries in the world with “Guinea” in their name; this is only one without an adjoining moniker). The country has a population of 13.5 million who are predominantly Muslim and speak French as the official language of the country, but more prominently a mix of several local dialects, such as Malinke, Fulani, Susu, that are no more familiar to your eyes than they are to my ears. Prior to coming here, I set my heart upon learning French and I am now 2.5 months into an education process that to date has provided me with enough functional vocabulary to get around. For all clinical conversational needs, there is a cast of neurology residents at the hospital who will be informally translating for me; for everything else, there is the Google Translate app.

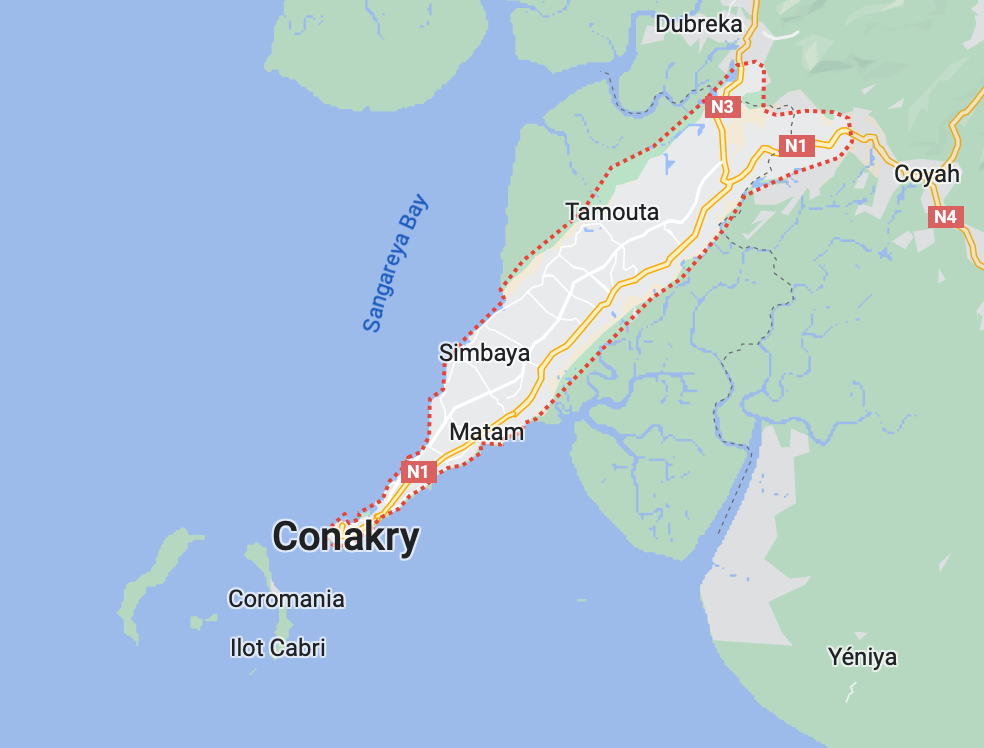

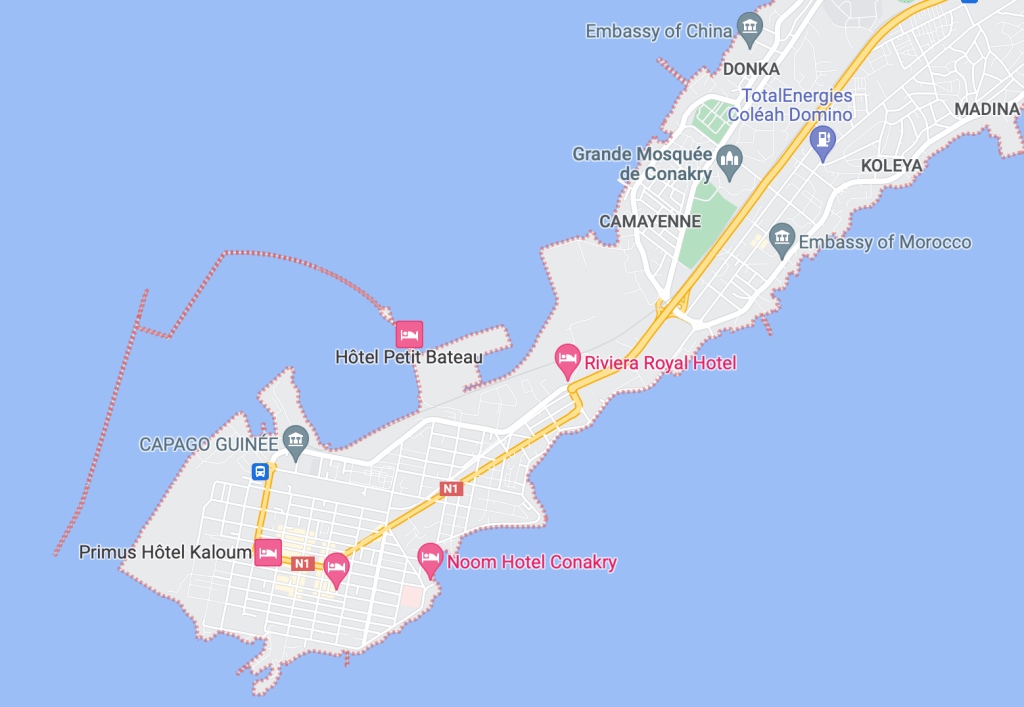

I’m staying at a reasonably comfortable hotel recommended by one of the local neurology residents in the heart of the downtown area. You may find the layout of the city and the area I am staying in below. While I usually like to take and share pictures when I travel, I don’t have anything to offer you from the last couple of days. Since arriving and meandering around the area, I have seen a grand sum of three potential foreigners and have not felt comfortable taking pictures on my smartphone in this very un-touristy area. As I walk along the streets, I feel eyes lingering upon me for a moment longer than usual, not so long that I feel like a true novelty, but long enough that I know it is unusual for a white man to be here. The children gaze for longer and with more interest, many of them waving and saying “bonjour.” There are also innumerable persons who are visibly handicapped, who almost inevitably approach with a smile and ask for something in a language I don’t understand. I have come to averting my eyes with ambivalence as I see them approaching to avoid the discomfort of denying their gentle entreaties.

So why have I come here? While there is a part of me that wants to give to every hand that asks, I am not so well-resourced, nor so opinioned, to believe that those offerings would make a real difference. Yet coming from the relatively limitless abundance of the Boston hospital system, I’m struck by the depth of the need for compassionate neurological care for children here and the possibility that I may yet do some real good for some of them. The research project and focus were mostly a means of getting here.

Today was my first day at the hospital, and when I set out this morning, it was with the belief that I was to be introduced to the head of their department of neurology, a colleague of the Principal Investigator that I am working with who is sponsoring my visit. Upon arriving, I was greeted without fanfare by one of the neurology residents who told me that I needed to start seeing patients. He then chauffeured me through a busy hallway lined with patients before he accompanied a mother and her child in, and then later another, after telling me, “they’ve been waiting to see you for six months.” The first mother spoke French, which now seems like a relatively easy history to collect, as the second spoke only Fulani, and so I collected my history by means of one of the neurology residents who spoke that dialect and then translate it back me in French through a smartphone application. After I had named the cerebral palsy and epilepsy that had struck her son but whose names she had never been heard uttered before, she said something to the resident that didn’t make sense, and so I asked him to translate again; he said, “she wants to know if you can take her child with you so he can get better care.”

I conclude by observing that nearly everything that could have gone wrong with my trip from Boston to Conakry did go wrong: my flight out of Logan was delayed; I had the door for a connecting flight from JFK to Paris closed in my face; I was stranded at 2:00 AM in New York with the next flight 18 hours away (leading to $200 in Ubers and an unplanned overnight at my parents); when I finally did get to Paris and then Conkary the following day, my luggage got lost somewhere in transit (it has yet to arrive, and I am still wearing the same pair of underwear that I put on last Thursday morning). Yet the funny thing is that, on my return to JFK from my parents’ place, the man who happened to be driving that taxi was from none other than Conakry. For all of the little mistakes that conspired to make me miss that flight to Paris, I found myself in the car of a man who was from the city I was destined to travel to, and enjoyed every minute of conversation of those 90 minutes in traffic. And so I still find faith in the universe and its mysterious workings, choosing to believe that there is a strange order and interconnectedness to things, observable only to those who look for it.

Until next time,

The Gringo

///