Mes chers amis et ma famille,

By this point in my journey, I hope you are beginning to grasp the depth of need for improvements in pediatric healthcare in this country. Of the more than 13 million people in Guinea, half are under the age of 15; for this half of the population, I have heard there are only 15 pediatricians in the entire country (that’s 1 pediatrician for every ~433,333 children, compared to 1:2040 in the US). There are good, hard-working people working tirelessly in medicine here, but the resources are limited and the magnitude of the problem is more than immense.

Whatever conclusions you have drawn about the situation in Conakry, their capitol, the need is even more dire elsewhere in the country. There are significant portions of this population that do not have access to medical doctors, frequently relying instead on traditional healers. Sometimes when things get really bad, there are families who will travel for days to reach a health care center, spending their funds on transit and chipping away at their ability to pay for the medical services they will be recommended. After such a trip, one of the children I recently saw in the hospital is gradually succumbing to the ravages of an infectious disease because his family has run out of money for antibiotics.

Prior to coming to Guinea, I had been put in contact with a pair of American doctors, who have transplanted their lives in Texas to build Guinea’s first dedicated pediatric center, outside of the capitol in a place called Dubreka. They are a church-based group with the mission of advancing the standard of pediatric healthcare in the country, who came here and recruited staff, and told me they hope to someday hand over the reins to locals. We continued to swap messages after my arrival and they helped me navigate this unfamiliar healthcare landscape, telling me what medications were available to prescribe and what community resources I could mobilize for my patients. When they asked if I’d be interested in coming to visit the hospital they are still building to give a lecture on neurology and help them manage a couple of neurological patients, I hopped on the invitation, curious to see the project but also excited by the new honor of being a guest lecturer.

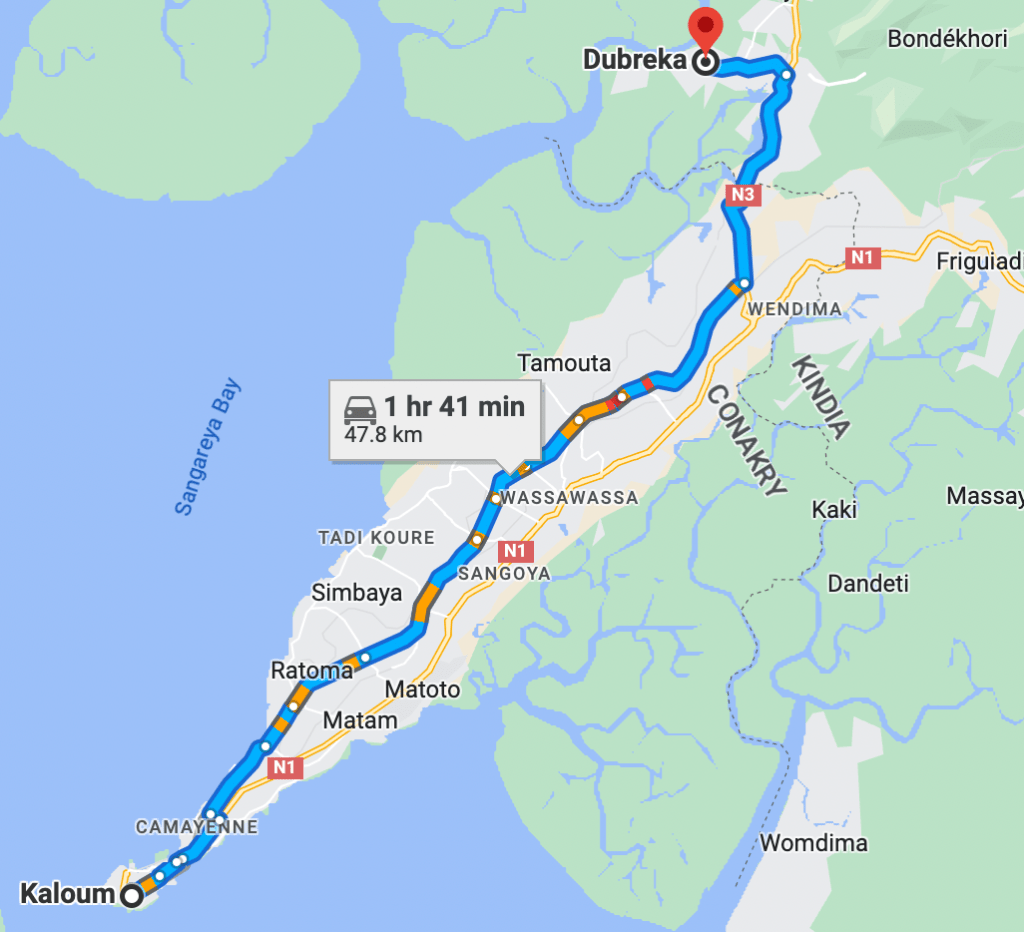

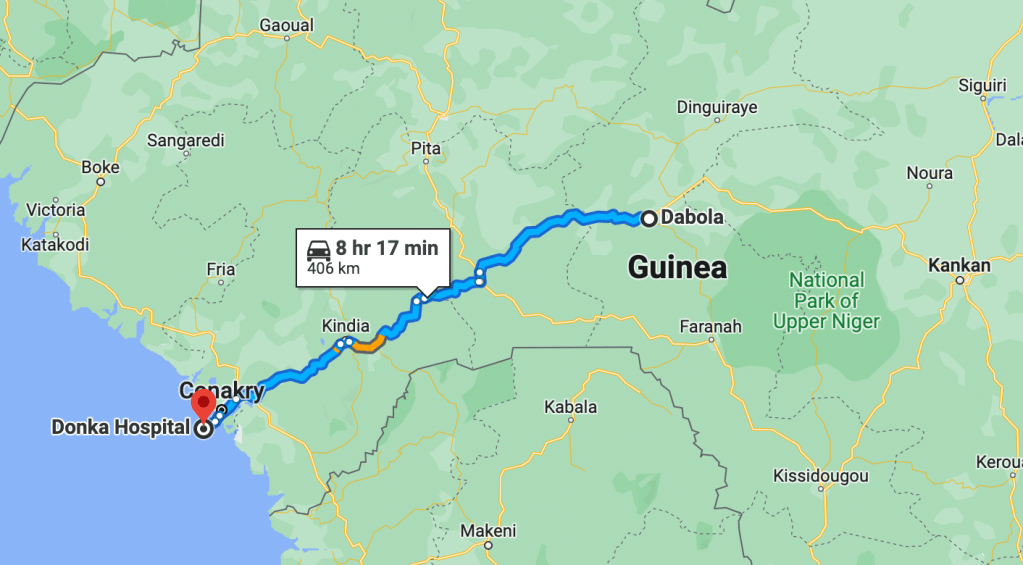

At the end of my third week, they arranged for me to meet at driver who would help shuttle me from the furthest corner of Conakry. I took a cab at 5:30 AM to meet the driver half an hour away because otherwise the two-hour commute would double in the morning traffic (Below, I have included a map of this journey, although Google typically doesn’t account for road conditions and tends to under-estimate travel times here; as a point of comparison, further below, I have also included a trip from Dabola, in the middle of the country, to Donka, the capitol’s biggest hospital, but note that Dabola has a “national route” (i.e., road) to access the capitol and this excursion could take far longer coming from elsewhere in the country). The adventure included the hiccup of losing cellphone signal at the rendezvous point (see above) and waiting nearly an hour in the dark with my backpack in a strange part of the city until the driver came looking for me (there is never a dull moment here). I dozed on the drive and when I first opened my eyes, I was greeted with the welcome sight of greenery: due to the difficulty of getting outside the capitol, scarcely had I ventured from my corner of the concrete jungle and scarcely had I seen grass, trees, or shrubbery.

The hospital compound was still under construction, but you could tell they had already laid the foundations for a modern pediatric center. We circled the compound until we were let in through a gate opening to an enormous courtyard that included the hospital itself, several unfinished buildings, and generously sized housing units. My driver escorted me to the latter, where I met one of my hosts and her lovely family, including her husband and one of three small children (the others were at a local school), a 5-year-old boy who was eager to show me his room and his toys.

Within 45 minutes of arriving, I was giving a presentation to the entirety of the hospital staff, with the assistance of the same host who sentence by sentence translated my lecture into French. I spoke about the structure and physiology of the nervous system and then gave an overview about seizures and cerebral palsy. This cumbersome process of presenting gave me time to be deliberate with my word choice, and watching my host push her French to its fullest ability by conveying low-frequency words in her neurological vocabulary banished any nerves I’d felt prior to the presentation. They applauded, asked good questions, and then thanked me. Having gotten the presentation out of the way, I was ready to see the six patients they had chosen for me.

Over the rest of the day, their staff watched me diagnose patients with stroke, psychosis, neurological complications of infectious diseases, help control seizures or improve the functioning of patients suffering from cerebral palsy. Every now and then I’d pause to explain what something on the physical exam meant, note what I was seeing in the shades of gray of a CT, or discerning from among the squiggly lines of an EEG. The picture at the top of this email is the staff watching me make a game out of the neurological exam with a patient who had developed hyperactivity, impulsivity, compulsiveness, and tics after an infection with Trypanosomiasis (the “African sleeping sickness”), but who was still remarkably intelligent, loved the US, and told me he wanted to be a doctor someday.

About five hours into the cases, I looked around at a room of tired faces and asked, “are you bored yet?” and was pleasantly surprised to hear a resounding “no.” After the last patient had gone home, one of the doctors thanked me again. “J’espère que vous avez appris quelque chose,” I’d said. “Beaucoup,” he replied with a smile. I went back to the guest apartment exhausted from performing. That evening, I joined my host and her family for pizza and a movie, enjoying homemade crusts and laughing when the same boy from earlier closed his eyes during the kissing scenes.

Early the following morning, I’d head back to Conakry accompanied by two ex-pats, a nurse and a pharmacist, who’d left America to dedicate the beginning of their careers to helping build the hospital in Dubreka. They educated me about the grim landscape of maternal-infant care and told stories about families having multiple kids with genetic illness (“due to pollution,” they speculated) or children getting washed away in flooding during the rainy season. The most tragic part of all this suffering here is that – with the high mortality rates, limited funding for pediatric medicine, and abundant poverty that for some leads to children becoming “just another mouth to feed” – it seems to be expected, almost. There is simply less value placed on the lives of children here than there is back home. Every day in the streets I see the physically disabled who remind me that someday these sick children will become adults…and what then?

By the way, that 6-year-old from my last installment, with the nasogastric tube and the issues with the antiepileptic management, was taken home in the same state by his family over the weekend so that they could seek the help of a traditional healer. After five weeks with continued worsening at the hospital, they had lost faith in medicine’s ability to help him. At night, I am kept awake by the ending that I fear his story will have.

As I write now, I am halfway through my final week in Guinea. There is still so much work to do here, and I am beginning to suspect that this kind of work is never really “done.” Yet if I can amplify my reach in this country with no pediatric neurologists by sharing what I’ve so far learned in my training with the healthcare workers and these families, then perhaps they can continue to spread this knowledge when I am gone. Now there are people in Dubreka who are doing everything they can here to make life a little bit better. And there are also little victories: a two-year-old who came to me after losing the ability to walk is now cruising again, and I know to that family those little steps mean everything.

To anyone curious, the website for the hospital can be found here: https://www.hopeignited.org/

Bien à vous,

Le Gringo

P.S. My medical supplies, which were supposed to be released on Monday, are still MIA. So much for the research, so much for free medications for the children…

///